An old, increasingly fatter, red nosed, white haired Briton rambles on, at length, about things Spanish

PHOTO ALBUMS

- CLICK ON THE MONTH/YEAR TO SEE MY PHOTO ALBUMS

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- Adriatic Cruise Oct/Nov 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

Thursday, July 13, 2023

Road Numbers

Friday, July 07, 2023

Not raising a glass but it is a toast

We took the scenic route. We stopped over for the night in Andalucia, in Córdoba, before heading on to Zafra, Mérida, Cáceres, Trujillo and Plasencia. It's a while since we've been so far from home in Spain and it reminded me of something I already knew, but often forget, those small but significant regional differences.

Toast for breakfast. Usual, traditional, commonplace all over Spain. Near to home toast is, usually, half of a smallish breadstick or baguette. Just the half, media or, if you want the whole thing entera. The most basic version comes dry and you self add the oil and salt. The next step up, pricewise, is to add a layer of grated tomato (in Catalonia they usually rub the tomato directly into the bread). Richer people add serrano, cured, ham and even cheese. In trendy spots they offer avocado too.

In Andalucia the differences from home are subtle. There is a tendency to flat slices of bread though "burger bun" molletes are also pretty common. Bread apart, the routine with oil and grated tomato is much of a muchness. Pork dripping, with or without paprika, wasn't on offer. In Sevilla and Cádiz it would have been. The next day, in Zafra, now into Extremadura, the tomato looked completely different. It had been mashed up with garlic and oil and then blitzed with one of those hand blenders. To be honest it looked a bit unpleasant. Our cats have been known to produce something with a similar colour scheme and texture. Fortunately I'd chosen to be radically local and I'd asked for the local paté, cachuela. Adding pork products to toast is big in Extremadura because of the fame of the local, cured ham - it's often quoted as the best in Spain. Maggie was stoic as she chewed on her toast with tomato. Next morning she wondered if they might have the Madrid (and ever so English) variant of butter and jam. In Madrid, where Maggie lived years ago, butter and jam was the norm. Usually in Madrid the bread has the same colour and consistency as a slice of Mother's Pride but three times as thick. Extremadura offered sliced bread too but from far less industrial looking loaves. In Trujillo they even offered brown bread. I wonder if there's a doctorate in this? Varieties of toast on the Iberian Peninsula.

about this thing of trying the local variant I should mention my consternation in not noticing something in Córdoba before I ordered. When in Rome and all that. There lots of people were having pitufos for breakfast. I've only ever used the word pitufo to describe what we Brits call Smurfs but in Córdoba a toasted sandwiches with oil, cooked ham and cheese is a pitufo. I understand that they're more typical of Malaga.

Now moving on to croquetas...

Sunday, July 02, 2023

On the difficulties of knowing what's going on

War in the Social Networks between the Gay idols of Vox and the activist known for his "Txapote would vote for you."

The first paragraph went on to say: The conflict, which is causing furore among streamers from the Extreme Right - the people who produce digital content in social networks - has reached the courts. The lawsuit presented by the YouTubers Carlitos de España (Charlie boy of Spain) and Madame in Spain, two of the gay idols of Vox, against Chema de la Cierva, the activist who menaced a team from TVE by shouting directly on air, Txapote would vote for you Sanchez," has had a trial date set.

The reason for this blog has nothing to do with the actual news story. It's about how difficult it is, sometimes, to have the faintest idea about what's going on around us; just how much information you need to decipher even a simple story.

Some of the basics I knew.

Vox is a far right Spanish political party. It is homophobic, racist, anti immigrant, super conservative and, basically, in my humble opinion, a party of dangerous nutters. They did well in the local regional and local elections and in several towns, cities and regions they hold the balance of power. In those places they have been getting close to book burning. No to LGTBI flags on public buildings, banning plays they don't like, changing the names of departments, cutting budgets and services etc.

Txapote was an ETA terrorist. ETA fought for independence in the Basque region of Spain by killing and maiming lots and lots of people. Txapote was one of ETA's mass murderers.

Sanchez is the current socialist President of Spain, He has pushed through various bits of legislation and maintained his coalition government with backing from, and doing deals with, several small parties with very specific agendas. One of those small parties has historical links with ETA. Think Sinn Féin and the IRA.

TVE is the Spanish State television broadcaster. They are always accused of being pro government by the parties in opposition.

It was easy to guess who Carlitos de España and Madame in Spain were. People who are Gay or Trans or whatever, the sort of people you would expect to be opposed the the policies of a group like Vox, but were, instead, outspoken and public supporters.

I knew the Txapote quote but I had no idea about the person behind it. Until recently Chema de la Cierva was one of the Vox faithful. De la Cierva was producing video blogs to support Vox and to distribute their message among young people. Apparently he got a bit fed up with the "soft line" the party are taking and he now claims that Vox owe him lots and lots of money. He has decided to join the Falange which was Franco's party; basically fascists.

I didn't know about his full outburst on the TVE telly programme Hablando Claro, Speaking Out, which went something like this: "The media at the service of the people....!! Txapote would vote for you, Sánchez! Socialist! Mass murderer! Son of a bitch!" and then he went on to the programme's team "Don't come near me or I'll kill you! Don't come near me, you TV motherfu**er! I'll beat you to death! Get out of my fu**ing town! I'll beat you both to death! You bloodsuckers! You sons of bitches!".

And the court case? Well apparently he had a bit of a go at Carlitos de España and Madame in Spain. "What next?", he asked, "Child abusers on the Right?"

So, now we know.

-----------------------------------------------

This is the actual text rather than my bastardised translations

Guerra en las redes de la extrema derecha: el agitador de 'que te vote Txapote' contra los youtubers LGTBI referentes de Vox

El conflicto que azuzó la atmósfera digital de streamers –creadores de contenido– de extrema derecha ha llegado a los tribunales. La querella presentada por los youtubers Carlitos de España y Madame in Spain, dos de los referentes LGTBI de Vox, contra Chema de la Cierva, el agitador que amenazó a un equipo de TVE y gritó en directo “Que te vote Txapote, Sánchez", ha sido admitida a trámite

Thursday, June 29, 2023

Two kisses and a big hug

The club is organised by the Pinoso public library, which is housed in the Centro Cultural - the modern building halfway up el Paseo de la Constitución, next to the Indian restaurant.

Like the majority of book clubs I've heard of, the plot is simple. The group reads the same book. I don't actually mean that - we have more than one. I thought to change the sentence to read that we all read similar books, but that doesn't work either. So I'll take it that you know what I mean. Anyway, after reading a book, the group comes together and comments on it. We have some, nominal, say about books for inclusion in the next "course," but really, the librarians choose the books using criteria like who's fashionable, mixing international, Latin American and Spanish authors, access to the books through the library system and slightly politicized things like not only choosing male writers.

The organization is pretty slick. We get a spiral-bound, bulky magazine-thickness booklet, which details the members of the group with contact details, dates of meetings, dates of national or international literary events, books that we'll be reading this year with a bio of the authors, a bibliography, the cover notes on the book, and any additional paperwork. It's comprehensive. The librarian and archivist who look after the group must put a fair bit of graft into its production. There are about fifteen of us in the group. I'm the only bloke, but I'm not the only Briton.

So when I joined, and I joined it as a language challenge, something a bit beyond my grasp, with the advantage of being local and with local people, I supposed that the process would be clean and simple. Read a book, in Spanish, turn up at one of the usually three weekly meetings, natter about the book, go home, and repeat the process. It turns out that the group life is much more involved than that. There are quite often book launches from local authors, and the club gets involved in those as well as things like World Women's Day or World Poetry Day. There are sometimes little outings to do with a book that we've read or an author visiting a nearby town. I've found that there have been nearly as many ancillary meetings as scheduled ones. Naturally, being Spain, the group has its own WhatsApp group, and that too can be most amusing.

I taught English in Pinoso for two or three years. In that time, quite a few local people passed through my classes, but it's only very occasionally that I see any of those old students. On the other hand, when I'm out and about in Pinoso, I keep bumping into members of the book club. I don't know why, but the book club people seem to be everywhere. It's rather nice. They're a good bunch, and they've been very kind about my faltering Spanish.

Anyway, at the beginning of this month, as the sort of end-of-course do, the group - well, the librarians - had taken the opportunity to organise a Q&A session with a writer called Elia Barceló. I read something of hers for the session, but before that, I'd never even heard of her. Her Wikipedia entry suggests that I should have. She's both well known and well regarded.

She did her session with us, and then, as we are in Spain, we went to a bar to eat and drink. I wasn't at the same table as the writer, and when the people at my table started to go home, I got ready to leave too. I thought it only good manners to say goodnight to our guest of honour even though I hadn't said a word to her all evening. The writer was effusive when she said goodbye to me. I suspect she was probably impressed by the good humour and bonhomie that the Club de Lectura Maxi Banegas generates and that she'd had a good evening.

Friday, June 16, 2023

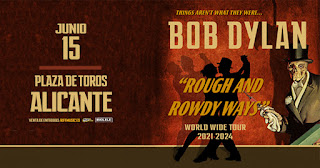

Dylan in Alicante

Thursday, June 15, 2023

Porky pies

At any traditional till in a Spanish supermarket, particularly in rural areas, you will notice that the person in front, generally, has ingredients and not the finished product. We're not talking extremes. Spaniards buy crisps, not raw potatoes. It's very unlikely though that they would buy a ready made lasagne. They cook from the raw materials. There are nowhere near as many packets, cans and jars of prepared foods as there are in the UK.

I've been making the midday meal for a while using a British cookery book. The book often lists a packet of this or a jar of that as one of the ingredients. As those packets and jars are not available I have to buy individual ingredients to simulate the packet or the can that the recipe suggests. Sometimes it simply has to be a substitute because, Jim Lovell and Apollo 13 like, if the recipe calls for mangetout, tarragon stalk, pak choi, hoisin sauce, tahini, harissa paste or even chilli flakes (all, obviously as British as jellied eels) then we have a problem. Then there are things that have similar names to a British product but they just won't do for the recipes. They are products designed for a local market. You can buy a jar full or a yellow powder called curry in any Spanish food retailer. The taste is like the curry sauce I used to get on my chips at the chip shop. It's not even a distant cousin to a Sharwood's or Patak's like curry powder that the recipes call for.

One of the key aspects of a capitalist economy is that if there's a market someone will be ready to exploit it. Carrefour, the French chain, is a big player in Spain and all of their stores have an international food section - malta for Ecuadorians, sauerkraut for Germans, dill pickles for Poles, Batchelor's mushy peas for Britons and so on. Even a small Spanish supermarket will usually have a few foreign things if they perceive a market. In Pinoso the local Consum supermarket has Warburton's crumpets, Oxo cubes, Heinz sandwich spread, HP sauce, Tetley's tea, Cathedral Cheddar and lots more. Some of the things we think of as British are readily available but with a different name. Gary Lineker could advertise Lays crisps for instance and Fontaneda digestives still have McVitie's baked into the biscuit. Other things, like Heinz tomato ketchup or Pepsi Cola, and tens of others, are international and thousands of others products are, as you'd expect, from tomatoes and oranges to canned tuna and chickpeas.

As well as the Spanish shops carrying a few foreign items there are occasional "foreign" shops selling food that Spaniards don't, usually, eat. Russian and various South American shops are reasonably common but, in this area, we Britons, even though Brexit is sapping our strength, still have the upper hand. It was curry paste that we needed. Making up a curry paste from scratch is just a bridge too far. Besides which Maggie had complained that the Spanish sausages in one of the recipes were too meaty; we needed the British product, full of rusk and recovered meat. The British shop we went to, like so many others, was a bit odd. These shops nearly always look understocked. I think that's probably because they are not expected to provide the staples. They specialise in those British things that people miss. Pork pies, ploughman's pickle, Bombay mix, Marmite, mango chutney, spaghetti hoops, custard creams, Paxo stuffing, Bird's custard powder, dandelion and burdock pop. Anyone wanting eggs, potatoes, sugar, coffee or apples will go to a normal supermarket. I suppose, understandably, because they are at the end of a long supply chain, with everyone taking their profit, the prices in the British shops tend to be quite high.

I should be fair and say that where there are larger populations of Britons there are supermarkets that look exactly like supermarkets and not like grocer's shops. Iceland for instance is involved in something called Overseas Supermarkets and Tesco has some outlets too. They have lots of stuff in tins and packets. They have piped music, the staff wear uniforms and they sell harissa paste.

Friday, June 09, 2023

Realising there's still a long way to go

Thursday, June 01, 2023

Good wine is a good familiar creature if it be well used

I don't know if you were made to read Shakespeare at school. I was. Shakespearean characters drink lots of wine. The wine they drank would be like a wine that is, nowadays, produced in just a handful of bodegas here in Alicante province. It's called Fondillón. I like it. It's price shot up when hordes of pesky wine reviewers discovered it and gave it big points scores so it's a while since I tasted it.

In the distant past a standard form of vineyard tenancy agreement lasted as long as the original vines were still in production. Vines produce fewer grapes over time so growers uproot old vines and plant anew. To maintain their lease the growers left some of the original vines in place. These old, tired plants were hardly worth harvesting so, by the time the grapes were cut from the vines, they had withered and were raisin like.

Fondillón is made from monastrell grapes. Fondillón has to have at least 16% volume of alcohol. To the casual drinker Fondillón has similarities to the sweeter sherries or ports but its high alcohol content, unlike theirs, doesn't come from addeing alcohol to the wine base. The alcohol comes from the high sugar content of the raisined grapes. The grapes are mashed up and the yeast on the grape goes to work turning the sugar into alcohol. There's a lot of sugar so the alcohol content gets up to between 16º/18º. That amount of alcohol kills the yeast and the fermentation stops. This process takes about three or four weeks. There is still plenty of sugar left in the mix which is why Fondillón is sweet. This newly fermented wine is added to barrels which hold similar wine from earlier harvests.

To be called a Fondillón the wines have to be aged in huge, old oak barrels for at least ten years; it's the long ageing that makes the wine what it is. The wine is produced using the solera method where wines from different vintages are mixed together to ensure a uniformity of style. If you've ever drunk sherry, decent sherry, not the stuff that Auntie Gladys has at the back of the sideboard from last Christmas, you'll know that it doesn't have a vintage, a year, on the label. That's because it's a blend of the wine from several years. The date on the Fondillón label, if there is one, is the date that the barrel was first laid down. It's an expensive wine to make because it has to be stored for ages, often for decades.

When it's time to sell the wine about a third of the amount in the barrel is drawn off. Obviously enough it's drawn from the bottom of the barrel and one of the Spanish words for bottom is fondo which is why the wine is called Fondillón.

Fondillón nearly died out in Alicante. Around the turn of the 20th Century an insect plague, phylloxera, devastated European wine production. It hit France first and the Spanish wine growers grabbed their opportunity to sell their product to drinkers left thirsty by the French. The low yield Fondillón vines made no economic sense at all. Fondillón production collapsed, Then phylloxera hit the Spanish vineyards and reduced production to a trickle. Nobody produced Fondillón. A chance meeting of two men in the Primitivo Quiles bodega in Monóvar, where there was still an old barrel of Fondillón, led to the wine being produced again in tiny quantities. In time production spread to a few more bodegas in Monóvar, Algueña, Pinoso and Villena. Our bodega in Culebrón makes Fondillón.

So, if you fancy supporting a world class wine with local history you know what to do. But don't expect it to be cheap.

Saturday, May 20, 2023

The art of simultaneous talking

It's local and regional election day next Sunday, the 28th, and the local politicians are doing the rounds. This post came about as a result of one of the meetings I went to.

We got the usual sort of presentation from politicians on the hustings - lauding their party's past record and future plans with the occasional disparaging side comment about the meagre offer of the other parties.

My Spanish coherency seems to be on hold at the moment and even my understanding is faltering. I'm hoping for a comeback but the slough has been a long and depressing one. So, as the politicians spoke, I only just kept up with the patter. Then came a comment which gave space for a local question. The meeting turned into a bunfight - claim and counterclaim, suggestion and rejection. Red faces and aggressive body language. I lost the detail completely but the broad stroke of the conversation was easy and it wasn't friendly.

In the Anthropocene past I used to run community buildings and my life often seemed to be one long committee meeting. A colleague suggested that the art to running a successful committee meeting was to get everyone to talk themselves out about something that anyone could have a valid opinion about - hand dryers as against paper towels, whether the vending machine should stock sugary snacks - just before you introduced the item or project that you wanted to push forward or stymie. It was a bit like that at the meeting but in reverse. We didn't get to talk about local concerns or the bigger questions because it was time to air old grievances. Conclusions were not reached.

I've often been impressed with how Spaniards handle themselves in large group conversations. Three Spaniards can easily maintain four conversations at once. It's a bit like that quiz show University Challenge where, sometimes, the contestants interrupt the question to answer. There the contestants guess at what's coming next to score points. Usually English speakers let someone finish their phrase before launching into the next. At times, amongst we Brits, there is a bit of a race to be the next to make the most erudite or argument winning point but, once someone is speaking, the rest hold fire, breathlessly awaiting their turn. Not so Spaniards. The person making the point may respond to two or three challenges or suggestions at the same time, turning from one conversation to the next with a dexterity as inbred as the ¡viva! call and response. Something Pavlovian. And of course, around here, when the raised voices and gesticulating starts you can guarantee that someone will break free of the Castilian chains and let loose in Valenciano.

I left the meeting a little early but long after it had finished.

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

My dad used to cut us in half wit' bread knife

It made me wonder about other things that have largely disappeared since I first started wandering around Spain. It also made me feel very old as the first time I came to Spain was over forty years ago. To be honest lots of the changes are just universal European changes - the disappearance of things like fax machines, floppy discs, dial telephones and typewriters. Some though are much more Spanish.

The first thing that came to mind, and where else but in a bar, was the floor sized waste bin. Bars were places for men. Women wouldn't be idling around in a bar, instead they'd be at home wearing one of those wrap around aprons getting the lentejas (lentil stew) ready. Plenty of bars didn't have bar stools so it was normal to see lots of men leaning against the bar snacking on something as they drank beer or wine. They would use those completely useless serviettes made out of some sort of liquid repellent paper and throw them on the floor along with their fag ends, nut shells, olive pits and shrimp peelings. Every now and then a waiter wearing a yellowed, bri-nylon, sweat stained armpit, once white shirt would push a broom along the floor to snow plough away the detritus. There were very few women servers in bars in the 80s.

In bigger towns there were street corner tables, card tables or upturned orange boxes, selling small, cheap, everyday items. I used to use them to buy single cigars but they were good for things like shoe laces, matches and tissues too. This was long before people needed a plastic bottle of water to survive leaving the house. There were far more pavement kiosks too selling a multitude of small things.

There wasn't a vehicle in Spain without a dent. Once, in Valencia, I was sitting outside a bar when a biggish van found that it couldn't get past because a badly parked car. The van driver got out of his van, looked at the gap, looked at the width of his van and started to boot in the corner of the offending car. The instant bodywork remodelling gave the van driver the extra few centimetres he needed to get by. When the car owner came back he glanced, and I mean glanced, at the dented in bodywork, got in his car and drove away. Oh, and it was a national sport to break into cars if there was anything of value on show. As a preventative measure people used to walk around with their car radios hanging, like handbags, from their wrists.

Puddings were another thing. Menús, not menu as in a list of things to eat in a café or restaurant, but menú, as in a set meal, had a very limited range of options but the puddings were even less varied. Flan (a table creeper), natillas (vanilla custard), ice cream and fruit of the day. Never anything else. Oh, and the wine was always so rough that it came with Casera (sugared, fizzy water). And of course everyone everywhere smoked. Between courses, in the doctor's and as you queued at a train station ticket office. Even as late as 2005, when I finally moved here, there were chain smoking people behind the desks in places like the Traffic Office.

All our local knowledge perished when we left the UK. We needed lots of things for our new house but finding them was hard. If we wanted a locksmith or a plumber or an exotic masseuse we couldn't ask on the Pinoso Community Facebook page because there wasn't one. Our British solution at the time would be Yellow Pages but the Spanish version was useless. It drove me to distraction. Everything was "organised" into towns. That meant we had to trawl through locksmiths in Pinoso, none, locksmiths in Monóvar, none, locksmiths in Petrer etc. Once I'd found a number and plucked up the courage to ring, phone calls in a foreign language are tortuous, most of the numbers were incorrect anyway.

There were so many things. Women dressed in black as a sign of mourning for their dead husbands. Women shuffling, on their knees, towards the altar in church as some sort of penance. Hotel rooms with washbasins and clean sheets on the bed but otherwise almost bare. Just two television channels with the national anthem sounding over the fluttering flag at midnight until 1990 when the commercial channels began regular broadcasts. In Galicia in the 1990s donkeys and carts were still common and because not everyone had access to a car you could catch buses from anywhere to anywhere. Oh, and a train journey from one place to another could take ages. I remember a trip between Seville and Alicante with a compartment load of drunken squaddies, just released from compulsory military service, that took around 12 hours.

And, of course, you could ride into town on the tram, buy a fish supper for your girl, get a bag of sherbet on the way home and still have change from a farthing. And if you told young people that today they wouldn't believe you!

Wednesday, May 03, 2023

And Running with Horses

The photos were in focus, the viewpoint was safe and I was able to talk to a family from Llano de Brujas who were leaning on the same wall But after about ten horses had run past I thought I'd have a bit of a wander and see if I could get some nice, safe, snaps of the horses as they arrived at the top of the hill. It was the first time I'd done that. Interesting. Injured horse handlers, crying horse handlers, girlfriends greeting their hero horse handlers. The horses looked happier too now that nobody was poking them with a stick and demanding that they run through a red and white coloured mob of shouting people. My personal favourite chant was "It smells of armpits here" - it did.

I had seen enough horses and decided to leave so I had no option but to join the throng of people on the slope as the only route to get to the signed emergency exit, the way back to my parked car. It wasn't so easy pushing my way through hundreds and hundreds of boozed and drugged up young people enjoying themselves with just a tad of danger to spice it up a bit. In fact I found myself caught up in this ebb and flow of bodies long enough for about five horses to pass. I have to be honest, I was glad when I reached the way out. I thought I might be there for the whole event. Some of those snaps with the bits of horse showing above the mass of red and white are in focus.

The Caballos del Vino, the Wine Horses, is something that happens every 2nd May in Caravaca de la Cruz. There are about 70 groups, peñas, and each one has a horse that takes part in three contests over the three days. The 2nd May is the big day though. Like baguettes and dry stone walling this event too is Intangible Cultural Heritage. The story goes that the Castle/Church in Caravaca was under siege by the Muslims, the Moors, in the middle of the 13th Century. Caravaca is called Caravaca de la Cruz because the church there has a piece of the "One True Cross". Not letting the Muslims get their hands on such an important Christian relic was considered to be top priority. The defenders had emptied their water cisterns so a group of Knights Templar decided to run the siege and take them something to drink. They couldn't find any water (!) so they loaded their steeds with wine skins and charged, bat out of hell like, up the slope taking the besiegers by surprise. They made it into the castle and the defenders, being well pleased to have a bit of something to slake their thirst, decorated the horses with flowers and suchlike.

The 2nd of May celebrations are dedicated to the One True Cross. Before the horses start running there is a floral offering taken to the church. Then it's the popular bit. The horses, wearing incredibly intricate embroidered mantles, start from a flat spot below the castle and run up a slope to the castle gates. The horses have four handlers, two on each side, and it's a simple time trial to run from the start to the finish. The starter says such and such horse can run, the four handlers try to get into position before they cross the start line and then horse and handlers run up the hill, it takes a few seconds. Caballo en carrera, racing horse, is the warning to the crowd. If you don't heed the warning four blokes and a horse may trample you to death. If the handlers arrive at the finish line still attached to the horse then the run is valid. Keeping up with the horse can't be easy especially as there are several hundred, possibly several thousand, people in the way who have to move to one side to let the horses pass.

Caravaca is pretty lively on the second of May.

Lots of pictures in the May album

Walking with sheep

Dry stone involves building things with stones that are not bound together with mortar. The things don't fall down because the stones are naturally interlocked or because of the use of load bearing structures. Dry stone techniques use rough, field, stones. So, for instance, Inca temples built without mortar but with dressed stone are not considered to be dry stone structures. Wherever you come from I'm sure you know dry stone structures.

Dry stone is most commonly used to build boundary walls but the technique can be used to construct anything from a way marker to a corral or a building. Around here the terraces (bancales in Spanish) are bounded by and held up by dry stone walls called ribazos. It's usually assumed (partly because they were responsible for so many agricultural improvements) that the bancales and ribazos, were built by the descendants of the North Africans, the Moors, who invaded Spain in the 8th Century. The problem is that field terraces use the local earth and field stones so that it's tricky to say whether they were built last year, last century or last millennium. Accurate dating of the terraces requires archaeological excavation. It turns out that the oldest terraces around here are Bronze Age, lots more are Moorish but the majority were actually built in the last three centuries.

The use of the bancales also varies. We logically assume, quite rightly, that terraces make hillsides easier to farm, and reduce the amount of soil carried away during torrential downpours. There are, though, other reasons for levelling the land. For instance, in this province, archaeologists have found that some of the Bronze age terraces were constructed as defensible positions to protect herds and flocks of animals as they were moved from pasture to pasture. This system of moving animals from higher to lower ground, from winter to summer pasture, is called transhumance.

Transhumance has always been important in Spain, more important in some parts than others. In the 13th Century Alfonso X, the Spanish king, defined a series of tracks and routes and a whole load of rules and regulations to stop conflicts between the nomadic herders and more settled farmers. The rules defined the characteristics of overnight resting places, widths of the tracks etc. It's these ancient rights that still protect these paths as public spaces today. At their height, there were over 125,000 kms of tracks in Spain.

One of the reasons for the importance of transhumance was that, from the 15th to the 19th Century, Spain had a monopoly on merino wool. All that time the wool trade brought enormous wealth to Spain. It's usually the explanation behind huge houses in now almost abandoned villages. The fine merino wool was the best material, at the time, for making high value clothing like underwear and stockings. That monopoly was broken when the Spanish royals gave gifts of herds of sheep to their royal relatives in other countries. Also, around the same time, both the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon recognised the economic potential of the sheep and sent a few home as their armies battled it out in the Spanish Peninsular War. The Australian merino flocks are descended from that looted Spanish stock.

The tracks the animals move along are called vías pecuarias, cañadas and the big wide ones, the ones that have to be 75 metres wide, Cañadas Reales (Royal droves). In this area the big tracks are also called veredas. One of the most important routes that comes through Pinoso is the Vereda de los Serranos which starts up near Cuenca and goes on to Jaen. There are lots of branch tracks (just like our motorways, trunk roads and local roads). Most of the animals passing through Pinoso were headed for the coast around Cartagena.

In this area there is another link between dry stone and transhumance as well as ancient terraces. Field stones were used to build shelters, stone sheds, called cucos. They could be used by farm labourers at busy times to save travelling time and also for shepherds and drovers passing by on those rural rights of way.

If you're local and you haven't seen them there are lots of cucos to the left of the road that runs from the Yecla Road down to Lel in the area called el Toscar and there are more alongside the road from Lel towards Ubeda - there are others in various places but these are easy to see from the road. Monóvar has the dry stone mapped out on this link and every now and again Pinoso and Jumilla Tourist offices do something about their dry stone.

Friday, April 28, 2023

Visiting Parliament

Saturday, April 22, 2023

I ordered up a cup of mud

The short, strong, thimbleful of coffee is a café solo.

The short, strong coffee with a drop of warm milk is a café cortado.

The short strong coffee diluted with about the same amount of hot milk is a café con leche.

The short, strong coffee, diluted with hot water is a café solo largo (but, as foreigners, we can say café americano).

The name americano, for what Spaniards traditionally call café solo largo, for weak black coffee, is the Italian influence. Most Spaniards think we foreigners are strange for watering down good coffee so they are not too concerned about what we call it. It's just another odd thing we foreigners do. Americano never has milk. We are not in Starbucks or Costa Coffee with their funny ways; bucket sized cups and exorbitant prices.

The beans are usually ground alongside the hissing coffee machine. Grinding beans is noisy too. On very rare occasions you may be offered different beans. I can't remember the last time that happened but I have a pal who always asks if the beans are torrefacto, that's roasted with sugar, because she doesn't like torrefacto. They never are. Everywhere, well nearly everywhere, offers decaf beans nowadays. If you want decaf from the hissy machine you have to add descafeinado de máquina to your order - ponme un café solo descafeinado, de máquina, por favor or me pones or un café con leche descafeinado de máquina, por favor etc.

There are tens and tens of variations which are to do with the presentation and the amounts of water, coffee and milk. Here are just a few. Lots of people ask for their coffee in a glass (en vaso). Foreigners sometimes ask for a big cup (en tazón). Corto de leche means go steady on the milk and corto de cafe means easy on the coffee. If you want a strong coffee you can add, bien cargado de café. I understand that, in the modern world, lots of people don't care for cow's milk so you might need things like leche de soja (soy milk) leche de almendra (almond milk). If cows aren't the problem but fat is you might ask for leche desnatada (skimmed milk). If you want sweetener instead of sugar, which will come by default in sachets, ask for sacarina. Nobody asks for brown sugar. In Summer people pour their coffee over ice. Just add con hielo to your order.

The short, strong thimbleful of coffee poured into a glass which already contains condensed milk so that it looks like an upside down Guinness is a bombón. This may be a Costa Blanca and Murcia thing.

The short, strong thimbleful of coffee poured into a glass which already contains condensed milk so that it looks like an upside down Guinness and then with a splash of booze added is a Belmonte. Again specify the alcohol of your choice. This too may be something local to this area.

And finally an easy way to make Spaniards snigger, as you sip your coffee, is to repeat what one time Mayor of Madrid, Ana Botella, famously said: "There is nothing quite like a relaxing cup of café con leche in Plaza Mayor".

Saturday, April 15, 2023

Take the day off

That's because there is a slight, but important, difference in the thinking behind public holidays in the two countries. In one the idea is of a holiday entitlement and in the other the idea is that there should be a rest from work on a festive day. In England, each year, you get eight extra days holiday, on top of any work related holiday entitlement. If a public holiday happens to fall on a Saturday or Sunday then you will get the previous or the next working day off as a substitute. In Spain if the festive day falls on Saturday or Sunday then it simply disappears from the annual holiday calendar because work won't get in the way of you celebrating that day.

So, why is it that there seem to be public holidays all the time in Spain if the real difference is just a couple of days? One of the reasons is for the way that the Spanish territory is organised. We need to remember that Spain, the state, is made up of regions and municipalities. All three of those entities affect the holiday calendar. The state can set up to nine days of public holiday, the regions set three and the municipalities, two.

We'll get to the national holidays in a while but let's start with the municipal, the local, days off. Pinoso (the picture is the Pinoso flag) is a good example. It borders five other municipalities (Yecla, Jumilla, Abanilla, Algueña and Monóvar). All six of those municipalities get to choose two local holidays, nearly always based on some local tradition. It's more than likely that when Pinoso has a day off the other five won't. When people hardly ever left their home town this was hardly a problem but, nowadays, we often cross municipal borders to go to work, to use a gym or to do the supermarket run. That being the case you can easily find yourself caught out and come to the conclusion that Spain is always closed.

Now to the regional days off. Three of the municipalities bordering Pinoso are in the Region of Murcia. Each region has a regional day and each one is different. So when Valencia celebrates the anniversary of the taking of Valencia city from the Moors in 1238, on 9 October by Jaume I, Murcia will be hard at work. On June 9 on the other hand the Murcianos may well be wearing alpargatas and zaragüelles to dance in the street to celebrate the adoption of their most recent boundary changes while we Valencianos grind through the daily routine.

Another regional variation comes from the so called replaceable days. To get to these we need to talk about the national holiday calendar, días no laborables. Central government produces an annual list of public holidays. There can be up to nine. New Year's day, Good Friday, Labour Day (May 1st ), Assumption Day (August 15th), National Day of Spain (October 12th), All Saints Day (November 1st), Constitution Day, (December 6th), Immaculate Conception (December 8th) and Christmas Day (December 25th). If any of those dates falls on a Sunday they will not be included in the list for the year. As well as these days the government publishes, each year, a list of suggested days for public holidays. Remembering that regional governments can set up to three days off the regions may adopt some or all of these replaceable days. If they wish they can make regional substitutions. When different regions make different replacements this causes another variation. To give a concrete example one of the replaceable days suggested by the national government is the Thursday of Holy Week, Maundy Thursday in old money (see the quip?). The Murcia Region likes that and takes the Thursday. On the other hand the Valencian Community has a tradition of celebrating the Monday of Holy Week instead. Murcia's plan produces a long weekend before Holy Week and Valencia's a long weekend after Holy week, a Monday off that Britons often, wrongly, confuse with the English Easter Monday.

The days on that replaceable or changeable list always include January 6th, Epiphany, the day after the Three Kings bring Christmas gifts for children in Spain, the Thursday before Easter Sunday and San José or Fathers Day on March 19th. There are usually a couple of other suggestions which vary from year to year. None of those days will be a Sunday. That doesn't mean that some Sundays will not be celebrated as festive days. Easter Sunday is, a good example, as is Mother's Day which is always the first Sunday in May. Both are recognised festive days, in the same way as they are in England but none of them need to feature on workday calendars as Sunday is always a day off.

It's a system that lots of Britons find hard to get to grips with while Spaniards like the way it honours local differences and traditions.

Sunday, April 09, 2023

Villages, towns and cities

Most Spaniards would consider that a villa has much less economic clout, a much smaller population and far fewer services than a city. Strangely the Spanish capital, Madrid, is historically, just like Pinoso, a villa.

The Spanish Constitution divides national territory into three divisions: municipality (e.g. Pinoso, or Yecla), province (e.g. Alicante, or Murcia), autonomous community (e.g. Valencian Community or Region of Murcia). All the other divisions, used by the autonomous communities and in everyday speech, have a certain degree of willy nilliness. So comarcas ( a grouping of locations), mancomunidades (a community or grouping of municipalities), villas (small towns with privileges) and aldeas (villages), aren't quite so easy to differentiate as my English definitions may suggest.

Just as in the United Kingdom, where some places look like towns but are cities (Wells, St Aspath), while some towns, that seem big enough to be cities (Northampton, Reading), are still towns there is some confusion about what is what in Spain. So, here's my unofficial guide.

Aldea: According to the official dictionary, the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, is a centre of sparse population usually, without its own jurisdiction. Aldeas are not a legal entity. Ask a Spaniard what an aldea is and they'll probably say a rural village with very few houses and almost no people.

Pueblo: These are municipalities, with powers, but with a small population. According to the Spanish statistical office and based on a supranational definition, a pueblo has a population of fewer than 10,000 inhabitants with an economy based on things like agriculture, fishing, forestry and mining - the primary sector. To be a bit contrary a Spanish law from 2007 defines a pueblo as a place with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants located in a rural environment with a population density of fewer than 100 people per km².

Villa: Where this blog began. Why is Villazgo, one of Pinoso's biggest tourist draws, called Villazgo? Blame the Romans. A villa was a Roman centre of agricultural production. Originally a villa was a "manor house" with a few buildings and dwellings alongside. As the Empire crumbled, and rule from Rome weakened, some of these villas took on local powers; they developed a form of legal autonomy. Some might build a castle and maintain a small private army, there may be aldermen and mayors to govern and administer justice or maybe a distinguished board to distribute water rights.

Ciudad: In Spain, according to the Statistics Office, a ciudad has to have more than 10,000 inhabitants who are mainly dedicated to economic activities outside the primary sector – that is it's an urban area with a high population density and with economic (commerce, services and industry), political, religious, and a cultural life. With that definition we can understand those traffic signs that point us to the "Centro ciudad" - City Centre - even though we seem to be entering a big village or a small town.

Just to round things off pedanías are centres of population which depend, for governance, on a nearby municipality. Usually they are outlying villages to a town but sometimes they are identifiable centres of population in an urban area. Chinorlet is a pedanía of Monóvar, Raspay is a pedanía of Yecla and Culebrón, Paredón and Ubeda (and a whole lot more) are pedanías of Pinoso.

The photo, by the way, is of the signature of Fernando VII to say that Pinoso is no longer a pedanía of Monóvar

Wednesday, April 05, 2023

Local languages

Most of we rich foreigners who move here want to be good immigrants. We try to learn a bit of Spanish before we arrive. We try to learn more as we live here but, in this area, and in others, we find that a lot of the information is in a different sort of Spanish. In Pinoso, which is in the Valencian Community, it's called Valencian. Although nobody speaks Valencian directly to we foreigners we see and hear it everywhere

The current Spanish constitution says:

1) Castilian is the official language of the State. Every Spaniard has the duty to know it and the right to use it (Castilian is the language that is known worldwide as Spanish)

2) The other Spanish languages will also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities in accordance with their statutes

3) The richness of the different linguistic forms of Spain is a cultural heritage that will be the object of special respect and protection.

So Spanish, Castilian is spoken throughout Spain. Catalan is spoken in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community (where the variant is called Valencian). Galician is spoken in Galicia and some areas of Asturias and Castilla y León. Basque is spoken in the Basque Country and Navarre. Aranese (a variety of Occitan which is another Southern European language) is spoken in a specific region of Catalonia.

I fully understand why people speak Valencian. It's a local language, it's the language of the land. My Yorkshire accent shows where I'm from too. But it does make life trickier for we incomers. Often it's easy enough to catch the gist of Valencian if you speak Castilian, but it makes it all harder work. I also wonder sometimes if there is a bit of exclusivity about it. Back in 2010 the Regional Government did a language survey in their territory. They found that nearly 50% of the population speaks Valencian "perfectly" or "quite well" (in some of the Castilian speaking areas that figure was as low as 10%) and about 25% said they write Valencian "perfectly" or "quite well" (6% in the Castilian speaking areas). There are around 50 nationalities living in Pinoso. Only one of them naturally speaks Valencian.

The strength of feeling behind the various regional languages, Basque, Catalan etc., varies a lot in the different regions. Sometimes it's simply another language, something of local pride and heritage. Sometimes it's considered to be one of the building blocks of an independent nation downtrodden by an uncaring and power crazed Castilian speaking government based in Madrid. This is particularly reflected in schools where classes may have to be taken in the local language. Sometimes opting to take classes in Castilian might disadvantage pupils in other areas of the curriculum. It's all very complicated and the stuff of hundreds of arguments around dinner tables, on bar stools and in WhatsApp groups.

One of the manifestations of this linguistic plurality/chauvinism is in relation to local government workers - from librarians and teachers to surgeons and town hall clerical staff. Where there is a local language a public job profile usually includes a language profile. Even where the local language is not a specific requirement having it will bring quicker promotion and greater opportunity in general. In some communities nearly all the government jobs require the local language but all the communities have ways around this for the times when there are skills shortages. It can still be a huge stumbling block.

I know someone, a health professional, who has always spoken Valencian at home but couldn't take the promotion offered to her until she had passed the official Valencian exam. As Spanish exams tend to penalise errors rather than reward knowledge, her everyday Valencian cost her points. It took her a lot of studying for her to pass the exam. Recently three Spanish nurses working in Catalonia used TikTok to complain that their careers were stalled by the need for a high level (C1) Catalan language qualification. The nurses used a very common, everyday, swear word which gave the Catalan authorities a good excuse to talk about potential disciplinary and legal action against the nurses. The Health Care chief in Catalonia said "We must guarantee care in our local language". There was no mention of their nursing skills.

Sunday, April 02, 2023

If you want to know the time..

The structure and organisation of the Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad (Security Forces and Corps) is complex, so take this as a rough and ready guide rather than the definitive truth. I've omitted the blood soaked past and avoided any sort of critique so I apologise now if the post is a bit dry and dusty.

Nationally there are two police forces. The Guardia Civil and the Cuerpo Nacional de Policía (CNP). In very broad stroke the CNP operate in urban areas and the Guardia Civil operate in rural areas. The Guardia Civil use a green and white colour scheme while the CNP uses blue and white. Both add the Spanish flag into their livery. Both these national police forces are controlled by the Interior Ministry but the Guardia is a military unit with responsibilities to the Ministry of Defence.

In any town with more that 5,000 inhabitants there has to be a police force employed by the local Town Hall, these are Local Police or Policia Local. In Madrid they are called Policía Municipal and, in Barcelona, Guardia Urbana.

All the police forces do those things that you expect from European police - protecting people, goods and property, maintaining order, preventing crime, investigating offences and collecting intelligence about potential crime. The two national forces have different, but sometimes, overlapping responsibilities.

The CNP (68,000 officers) works in the provincial capitals and in specified urban centres; as a rule of thumb those with more than 30,000 inhabitants.The CNP issues identity documents and passports and has responsibility for combating drug crime, organised crime, cyber crime, gambling and forgery. They also do border control, immigration and human trafficking. They are responsible for coordination with international police forces and they control private security firms. Among the specialist functions the CNP has a bomb squad, a "SWAT" team, the GEOs, and more.

The Guardia Civil (78,000 officers) deals with traffic on the main roads, looks after the security of things like ports and airports, looks out for environmental crimes, moves prisoners around and issues all the gun and explosives licences. They have specialist units for anti smuggling, for tax related and economic crimes. The Guardia do mountain rescue and they patrol the southernmost frontiers of Europe in Ceuta and Melilla.

The Local Police (66,000 officers) look after the protection of local councillors and council property, deal with urban traffic, are responsible for crowd control at public events (along with Civil Protection), mediate in conflicts between neighbours and cooperate with the other police forces.

Now the exceptions. Because of Spain's almost federal structure there are a regional forces in Catalonia (Mossos d'Esquadra), the Basque Country (Ertzaintza), Navarre (Foruzaingoa) and the Canary Islands (Guanchancha). About 28,000 officers in all. The Basque and Catalan police forces do most of the jobs which are usually associated with the Guardia Civil and CNP within their regions. In Navarre and the Canary Islands the regional police forces are less "powerful" but they still have a very visible presence for day to day policing including serious crimes like murder. In Andalucía, Aragón, Asturias, Galicia and Comunidad Valenciana there are regional police forces that are part of the CNP but have a certain independence. If you live in Alicante you may have noticed the light blue and white police cars of the Valencian Police from time to time.

The title?, it was a song, If you want to know the time ask a policeman.

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

A bunch of grapes

Around here grapes are grown for eating and for making wine. Pinoso is a bit too high and a bit too cold, to grow eating grapes, but just down the road in la Romana, Novelda and Aspe they're all over the place. The eating grapes are easy to spot. The most popular variety is called Aledo and it is often grown under plastic, protected from the sun, birds, and other pests by paper bags. The bags slow the grapes’ development and produce a grape that's soft and ripe for picking at the end of the year. How very fortunate that one of Spain's most widespread traditions is that of eating twelve lucky grapes, keeping pace with the midnight chimes of the clock in Madrid's Puerta del Sol, as the old year becomes the new. Nearly all the grapes are from around here and in Murcia.

Around here grapes are grown for eating and for making wine. Pinoso is a bit too high and a bit too cold, to grow eating grapes, but just down the road in la Romana, Novelda and Aspe they're all over the place. The eating grapes are easy to spot. The most popular variety is called Aledo and it is often grown under plastic, protected from the sun, birds, and other pests by paper bags. The bags slow the grapes’ development and produce a grape that's soft and ripe for picking at the end of the year. How very fortunate that one of Spain's most widespread traditions is that of eating twelve lucky grapes, keeping pace with the midnight chimes of the clock in Madrid's Puerta del Sol, as the old year becomes the new. Nearly all the grapes are from around here and in Murcia.The grapes in the Pinoso area are for wine. Wine is made from mashed up grapes. Grapes grow in vineyards. They are harvested and taken to a nearby bodega, winery, where they are turned into different types of wine. Red wine, rosé wine and white wine can all be made with red grapes. Green grapes can only, naturally, be used to produce white wine. When people ask for a wine in a bar or buy a bottle in a shop they might ask by grape type or region. There is a sometimes a link between the region and the grape - for example tempranillo grapes are the most common for Rioja wines and Sherry is made with palomino grapes. On the other hand Chardonnay grapes are grown worldwide so a Chardonnay could be a wine from the grape's native Burgundy or from places as diverse as Chile, New Zealand and Sussex. Wine bottles always say what grape type was used to make the wine.

The most common grape variety around Pinoso is monastrell. Lots of other types of grape are grown here but monastrell is the local variety. Monastrell doesn't need a lot of water, it doesn't need decent soil and it can deal with enormous daily temperature variations. The monastrell vines are usually cut back to the bare stump at the end of each season. In the past, to attain a quality mark, the vines had to be planted in a certain pattern. Looking at the vineyards you can see horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines of plants. New regulations allow growers to use different planting patterns and still get the quality mark. It will take years for things to change so you can still show off your local knowledge by pointing out the vineyards, with the traditional pattern. You can, sagely, add that these grapes will be picked by hand so they will be used in better quality wines. Machine picking bruises the fruit. The vines planted so the tendrils can grow up a wire support are for machine picking. The wine made from these machine picked grapes is still largely exported in tanker lorries, usually to France, where it is mixed with the local wine to produce a much more palatable end product.

All over Spain certain types of food and drink are given a quality mark. The scheme is usually called Denominación de Origen Protegida or DOP. The idea is that the quality is kept up by specifying what the ingredients should be, where those ingredients should come from and how those ingredients should be processed. By keeping up the quality of the traditional product it's possible to maintain a premium price. The local denominación is Alicante but just over the border into Murcia we have Jumilla and Yecla too. So, the next time you have visitors make sure you buy at least one bottle with denominación written on the label and you'll have a ready made topic for that awkward conversational lull that happens, every now and then, even with friends.

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Raising your eyes unto heaven

For some reason traditional, as in traditional costume, seems to mean 18th or 19th Century. The first Levi's were made in 1853, but I suspect we're unlikely to see the local dance group, Monte de la Sal, in jeans. There's a certain unspoken aesthetic about what classic and traditional mean. Maybe it's the same with houses, traditional implies some sort of fixed time in the past. Apparently Alicantino houses, those from Alicante province, didn't change much in their basic construction or style from the 17th Century through to the beginning of the 20th Century and they're the ones that are tagged traditional.

In these standard Alicantino houses coloured facades are a big thing. If you've been to Villajoyosa you'll know about vivid facades but if you look around the central Pinoso streets, like Perfecto Mira, Maestro Domenech, Sagasta and Maisonnave, you will see that it's the same here but without all the fuss. Those traditional houses are built of mamposteria which is like dry stone walling but with lime mortar. First, you try to fit the stones together, like a jigsaw, and then you fill the spaces between big stones with smaller stones. To finish it off you bind the whole lot together with the mortar. The mamposteria walls are often very thick. When some families became richer they showed off their wealth by rendering the walls and then adding colour wash. In the end nearly all the houses ended up rendered and coloured. You still see houses in the countryside without render because that's where the poor folk lived.Another feature of these classical houses is that the windows and doors follow the form of the house. Sometimes, often, there is a central axis marked by a big, impressive, solid wooden door. The windows are arranged, symmetrically, around that axis with the same shape and number on each side. The window casements and door surrounds might be picked out in mouldings of a different colour. It's usual for the windows to be tall rather than square or horizontally wide. Exterior decoration frequently picks out the floor lines of the various storeys of the house. The ground floor windows are usually protected with fancy ironwork; the fancier the ironwork the richer the household. It's very common for the upper windows to have small Juliet balconies commonly sporting fancy floor tiles. Sometimes there are decorative tiles under the eaves too.

There are as many exceptions to these "rules" as there are houses. Over time people renovate their homes and these classical features are diluted. Coloured facades dull and peel, someone might to build with dressed stone instead of mamposteria. Sometimes a different need called for a different design, big doors at the end of the building often point to an entrance for animals with carts or carriages for instance. But, if you can. just look up from street level and I'm sure you'll notice that some of these features are there.